Over the past few years we have seen women’s sport grow exponentially. The advent of the Women’s Super League (WSL) in England has dragged the women’s game towards a greater equilibrium with the men’s game. There is still a long way to go, however, but over the last year or so there has been great leaps and bounds forward. A couple of years ago (possibly 2017) I walked into a pub in Edinburgh that I knew played sports on their screens, looking to watch a particular game of football. There was something different about the match on one of the televisions behind the bar and it took me a few moments to realise that it wasn’t the men’s English Premier League game I knew to be on prior to that which I wanted watch, but a top match in the WSL, involving one of the same teams. This was a first for me and an important focal point, I think, that a well used and much enjoyed watering hole on a main road in the Scottish Capital City, would be showing a women’s game instead of a men’s.

The past three months alone have seen new attendance records set for women’s football on more than one occasion. On the 9th of November 2019 England played Germany in front of 77,768 spectators. This is an all time high for a British game, on home soil. Apparently, more tickets were sold – 86,619 – but people seemed to have been put off by the English winter weather. Even in Scotland, last summer, before the ladies left for the Women’s World Cup, the team draw a record attendance of 18,500 for their send off game at Hampden Park, against Jamaica, which pushed their numbers unto an all time high. During the competition itself, 6.1 million people tuned into BBC One to watch the Pool D clash between England and Scotland, taking a 37.8% share of the audience. Scotland as a competitive nation in women’s football have done well to get to the World Cup, when you consider that their domestic league is still amateur. The players still pay to play for the top teams and some clubs struggle to provide adequate medical care. England, on the other hand, got to the semi-finals for the second time in a row, finishing fourth this time around, in France, having won the bronze medal four years earlier in Canada.

In the WSL itself, there has been a similar increase in attendances and viewing interest in the competition. Manchester City ladies hosted the Mancunian Derby, in September, against Casey Stoney’s newly promoted United side, which attracted a league record of 31,213 people. The following day Chelsea got over the top of Spurs Ladies’ team at Stamford Bridge in front of a crowd of 24,564, narrowly missing out on setting a second record over the same weekend. Last season’s average was 833, which just shows how quickly something can develop, if given the right opportunity.

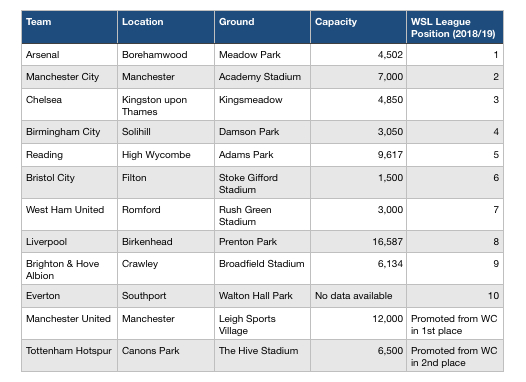

The WSL matches aren’t normally held at the same stadia as the corresponding men’s arenas. That particular weekend saw the English Premier League take a scheduled break for international fixtures, as is the norm, and the clubs saw the potential to earn some money, as well as promote the women’s teams and made use of the otherwise empty stadiums. This is an important element for the progression of women’s football, particularly the advancement of professionalism. In terms of equal pay, if clubs can gain higher levels of income from ticket sales and television money, sponsors will quickly get on board. If this happens, then I see no reason why the players can’t earn more money. Additionally, with increased wages, the top coaches will be attracted to the game and the subsequent rise in standard will become a productive cycle.

Most of the WSL sides that are affiliated to men’s teams play in different locations to their respective male counterparts. Manchester City are probably the best within the league for having brought the women’s team “in-house” where the ladies play at the club’s training facility, which is within touching distance of the Etihad Stadium. This is another part of the spectacle which can sometimes get overlooked. Fans want to enjoy the game from a comfortable viewpoint and the arena itself can add to the spectacle and help to create a good atmosphere and an enjoyable experience. Too big and it runs the risk of being empty, too small and you don’t get the benefits of the aforementioned additional revenue, or the ability to grow the business side of sport. What many WSL sides are choosing to do is to ground share with lower league men’s clubs, who have appropriately sized stadiums and are in a similar location.

I’ve heard criticism of the standard within the Women’s Super League, or more broadly women’s football in general. The comments that I’ve heard tend to be said without being specific to which league, team, or player that they are talking about. This is a view that I find to be ignorant to how women’s football has developed over the last 100 years, not only in the UK, but further afield as well. When you consider the lack of opportunity to play, the level of finances available for players, staff and clubs there will inevitably be an affect on the standard of coaching provided as the best coaches will tend to drift towards the higher wages of the men’s game. Therefore the rate of improvement within women’s football recently has been extraordinary. These attendance and viewing figures are proof that I am not the only sports fan that appreciates the WSL and British international football for the spectacle that it has become and for what it can be in the future. For me the WSL is something other sports should be looking towards, in terms of branding and development.

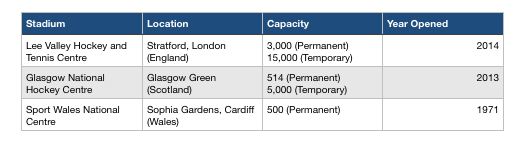

The Lee Valley Hockey and Tennis Centre, is a legacy facility from the 2012 London Olympics and is home to the England and Great Britain hockey squads. Since 2015 it has hosted a number of top level international events, including the 2015 EuroHockey Championships for both men and women, as well as the 2018 Women’s World Cup. It has a regular capacity of 3,000, which includes 500 seats under a roof. There is, also, the ability to increase the number of seats with temporary structures – something that happened during the World Cup last year. At this flagship tournament we saw up to 15,000 fans attend England matches during the competition.

Interestingly, during the World Cup attendances for women’s sport surpass the previous annual record across all sports of 682,000, an increase of 19% from 2016 to 2017 and a 38% increase from 2013 to 2018. However, this was a combined total for all sports played by women in the UK and doesn’t necessarily indicate a growing trend for hockey in particular. Although participation rates did improve within the sport after the women’s success at the 2012 and 2016 Olympic Games, spectator attendances at club level remain low within Britain. The simple reason for this is because there isn’t a culture of attending domestic league, or club matches, at least not in the same way as hockey fans do for top flight international matches. Something that I noticed during the World Cup last summer (I was covering the event for The Hockey Family, at the time), was that although England games as the host nation were selling out, the stands were largely empty for the other fixtures throughout the tournament. There is, also, a general feeling amongst the hockey media that there aren’t many people paying to watch games that aren’t already involved in the sport in some other capacity (player, umpire, coach, etc…). This being different from football, for example, which is very much a focal point within the mainstream media, that attracts those who have only ever watched games from the terraces, or as an armchair at home. This is something that women’s football may have benefited from.

More recently, Scottish Hockey hosted the 2019 Women’s EuroHockey Championship II, in August at the National Hockey Centre in Glasgow. This was the B-Grade tournament for European national teams and held at a legacy facility from the 2014 Commonwealth Games. Similarly to the World Cup held in London, the matches for the host nation were extremely well attended, if not quite at full capacity. Credit to the Scots on this one, this event was organised on a much better scale than those I have previously attended there. Fans seemed to have a good time, despite the wet weather, with plenty of food and drink kiosks involved and additional seating to get people through the door, thus creating a better atmosphere within the stadium. Over 2,900 bums were sat on seats, over the course of the week. Additionally, there were good viewing figures from across the various platforms. There are, in total, 362,387 views of matches streamed, including 44,854 pairs of eyes catching the coverage on the BBC.

Domestic hockey seems to be going through a revolution within the country as well, with changes being made to the top division in the hope to create a better brand of hockey. The new implementations have only started this season (2019/20), so it’s too early to make a judgement, but it’s an attempt to take a positive step forward. A change to the league structure is something that the English and Welsh can possibly look at as well. The centralised contracts, supported by National Lottery Funding, for those players involved in the Great Britain set up is good. However, it’s not going to be enough to develop a larger pool of players, similar to what the Dutch and Germans have coming through at their professional clubs. For me, we need to do more than just focus on the national team. There has to be a holistic approach to developing the sport. Fundamentally though, if we can get people turning up to stadiums and tuning into live streams then, the clubs and National Governing Bodies can sell sponsorship and reinvest the money towards the players and coaches.

As an observer of both sports, there are a variety of reasons why the English FA Women’s Super League is doing better than the domestic leagues in British field hockey. One is that although the English FA help to direct and guide and promote the league, the clubs are allowed to get on with things and develop at their own speed, within their own community.

These clubs are now showing that they have a growing ambition to interact within women’s sport and to engage with the fans and spectators therefore gain greater numbers of followers within the sports community. This has and will continue to get more people through the gate and potentially, amongst other things, earn money from women’s football. What I don’t see from within domestic hockey, within Great Britain, is that clubs are not promoting themselves enough. Although, the National Governing Bodies for hockey amongst the home nations have looked to improve the set up of league structures, clubs are not doing enough to put on an event for fans. Spectators these days have plenty of sports to choose from. It’s not just about meeting the price of a ticket stub, it is also about choosing to spend the time to attend over a busy weekend, it’s about having a shared experience with friends (some of whom may not be as enthusiastic about your preferred sport as you are), it’s about getting as many people through the door as possible in order to create an atmosphere and excitement around the event in question. This is what those involved with the Women’s Super League have been good at over the past few years. In a sporting world full of fan experiences, has the field hockey within the United Kingdom done enough at club level in order to create a sustainable fan culture within their sport? I’m not so sure…